Virtuous or virtue signalling?

Over years, brands have gained invaluable experiences in making adjustments to their branding strategies to stay relevant and appeal to their target audience, constantly working on their offerings, promotion and communications. From direct branding strategies (eg. visual and verbal brand elements design, etc.) to supporting branding strategies (eg. signature stories, branded content, branded entertainment, and so on), businesses have learned ways to safely interact with their consumers, and facilitate the brand-consumer engagement and participation.

However, recently we are observing the gradual migration of brands to new territories to feed their brand-consumer communications, where they don’t necessarily have experience. Brands are showing an increasing interest in addressing social issues and taking a stand, signalling they won’t be silent and are committed to fighting issues.

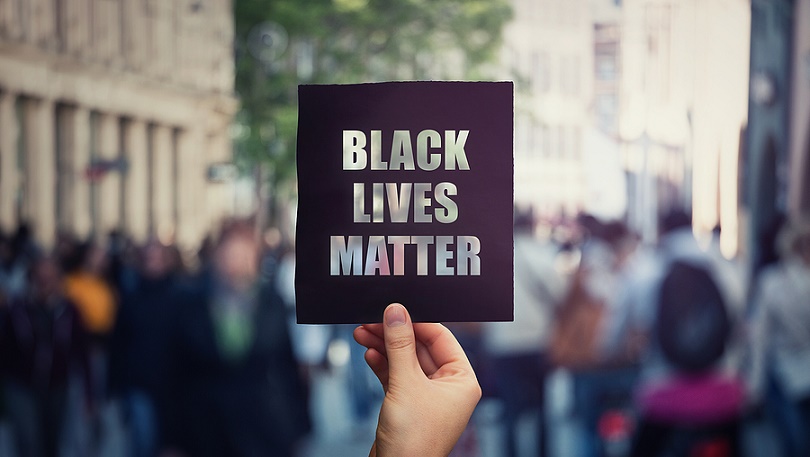

Over time, different social issues have become of great importance to the public, symbolised by movements such as Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Me Too. Brands that can be seen as social change facilitators and addressing societal and cultural tensions, may see such social movements as opportunities to meet expectations, build relevance and become iconic.

With their power in terms of financial support, product development, communication, public awareness, audience reach, and recruiting talent, brands can be an impactful agent of change. For instance, in light of the protests related to the BLM movement, brands started responding by delaying and reworking their campaigns, changing their logo colour, repurposing their tagline, expressing empathy and solidarity on Twitter and Instagram, and launching new campaigns.

However, businesses symbolically signalling that they’re ‘woke’ wasn’t enough to gain popularity. The general public wanted the corporate world to go beyond lazy responses and show real commitment. Many brands received backlash and mockery after their black square response to the BLM movement fell flat. But brands were quick to neutralise the backlash and make announcements that would promise a change in the organisation culture going forward. Adidas, for instance, announced that 30 per cent of future recruitment will be from black and Latino communities. Lush globally is currently in the middle of a 100-day plan where the business will achieve key goals towards greater diversity and inclusion internally.

Patient vs impatient wokeness

Signalling they are awake to important social issues, discrimination and injustice, brands have two routes to purposefulness and wokeness. Brands like Chobani or Dove, which adopted a higher purpose over time, are examples of slow-cooked, patient approaches towards showing commitment in tackling social issues, whereas ‘woke’ campaigns based on topical issues are impatient, short-cut approaches to making a difference in society. While the patient approach is generally perceived as more credible and genuine, impatient ‘wokeness’ is likely to be seen as opportunistic and inauthentic, and therefore most likely to backfire.

Should brands take a stand?

The short answer is yes, brands should take a stand. However, there are ways to increase the chance of being perceived as genuine. With call-out culture becoming the new norm, consumers are guarded and cynical towards such virtue signalling practices. So taking a social stand must be a costly exercise, evident by the level of corporate investment in the fight against the issue rather than just changing the logo colour. A key factor is the degree of impact and in woke moves. A US$1 million investment relative to US$15 billion won’t be perceived as impactful and will generate backlash.

The lack of practice in what is being supported and advocated for is also another driver of backlash, which can be neutralised over time by practising and walking the talk when it comes to tackling social issues.

If a brand like Gillette is concerned with gender equity and toxic masculinity, they have two approaches. One is to jump on the Me Too movement and invest in a TV commercial, lecturing the community on gender equity values (the impatient approach). The other is to start practising gender equity in their requirements and gender wage gap, reviewing the pricing of gender products, giving voice to different genders, sponsoring gender-diverse programs and so forth (the patient approach). Over time, the chances are the latter approach will bear fruit and have long-lasting brand impact as an agent of change.

Dr Abas Mirzaei is a senior lecturer in marketing at Macquarie Business School.

Comment Manually

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No comments